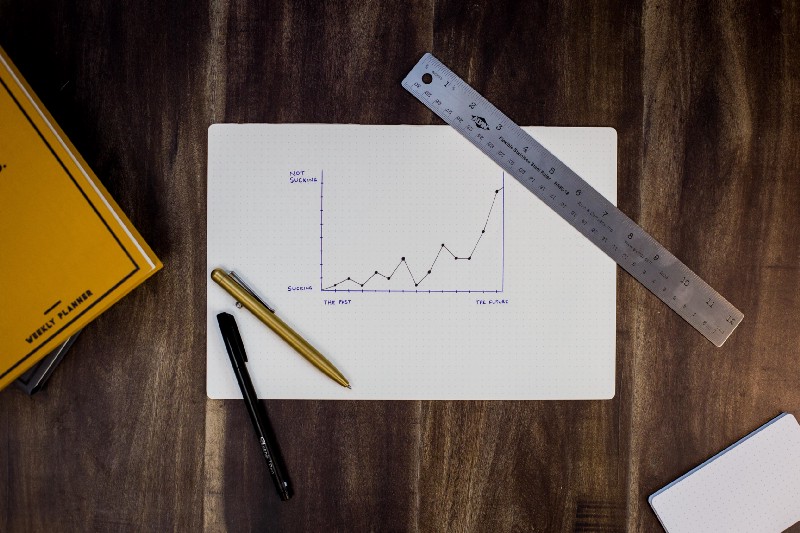

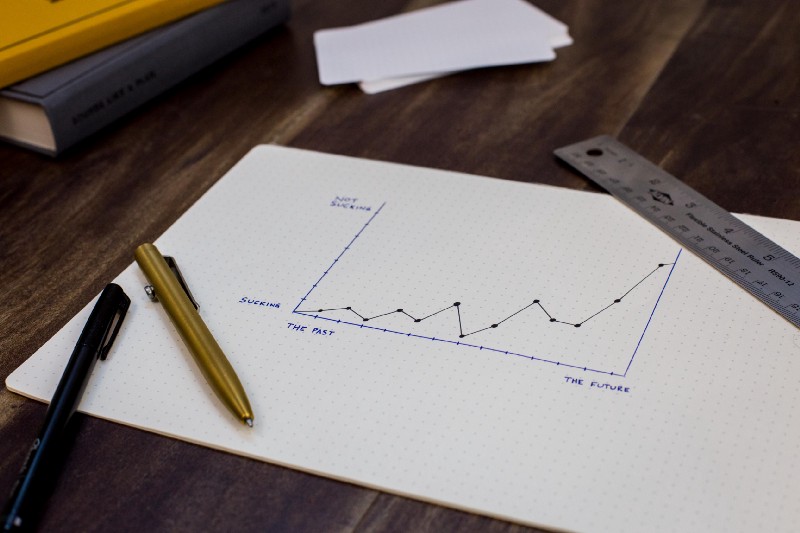

Watch out for these unexpected negative outcomes of measurement

It’s important to find healthy ways to measure

In the book “Dynamics of Bureaucracy”, Peter Blau reports this case in a federal law enforcement agency that investigated business establishments where there was an imposition of a quota of eight cases per month for each investigator. Toward the end of the month, an investigator who found himself short of the eight cases would pick easy, fast cases to finish that month and save the lengthier cases till the following month. The priority of the cases for investigation was based on the length of the case rather than urgency.

Book Title

by Authors

Identifier

This is a good example of Goodhart’s law:

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” — Goodhart’s law

Why does this happen? This happens because people ignore the fact that measuring affects the behavior of the people and you can’t choose your measures solely based on your information needs, but also on the effect you want to cause.

So, you want to align your measurement choices to your information needs, but you have alternatives of measures and you have to select those that will either not exert an influence over people or will influence their behavior positively, in the direction of achieving your goals.

The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”— Campbell’s Law

Which measures to choose?

Honestly, the first thing I would ask you before attempting to answer is “what do you want to achieve?”

The biggest mistake I see organizations doing is trying to measure everything they can. Tom DeMarco once said “You can’t control what you can’t measure. That is absolutely true in software, it doesn’t mean you have to control everything.

The second big mistake I see organizations doing is analyzing all the data they have just because they have it.

Measurement is expensive and can be harmful. It requires careful consideration and a lean approach. You want to align your measures with your organizational goals based on your information needs.

However, if you already know your goals and want to consider some measures, I’ll leave you some references here:

Book Title

by Authors

Identifier

Book Title

by Authors

Identifier

Also, I have some good posts with examples of measures and how to analyze them:

SEM Blog | Quantitative Software Quality Management — Part I

SEM Blog | Quantitative Software Quality Management — Part II

SEM Blog | Customer Support for Software Engineers — Part II

Here be dragons

If you like this post, please share it (you can use the buttons in the end of this post). It will help me a lot and keep me motivated to write more. Also, subscribe to get notified of new posts when they come out.

With alignment between your organizational goals and your measures, you naturally avoid collecting and analyzing things you don’t need. Without alignment, here is what you should watch for:

- Your measures become the goal.

Nobody knows the goal, so the goal becomes “to improve the measures.” See Goodhart’s law. That’s when the number becomes more important than the goal.

I once worked for a company where software development was a support activity, and the company wanted to cut costs. In the software development area, they decided to reject 20% of the lowest priority projects, because they were looking at the costs — and decided to cut costs. Was that aligned with any goal? Obviously not.

Well, remember topic #5? Many business initiatives got hindered or stalled, and revenue from these initiatives didn’t realize. The software costs were 1% of the organization’s cost. So, almost nothing was saved, the organization lost revenue, but the costs were cut. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ - The measures are not maintained.

Since you have no clear goal, you don’t think about how to evolve your measures. You also don’t question their value, and you don’t know when to deprecate them. - You don’t know what to do with the measures or you abandon them.

Many of your measures will either provide you with no actionable information or no value at all. Eventually, you will abandon them, because measuring takes time. - You don’t know what to do with the measures, but you try anyway.

And as a consequence, you spend effort in fixing what doesn’t need fixing, wasting your precious time (and time from others). If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. - Local optimizations do not always translate to global optimizations.

Let’s say that during your development process you update an artifact that your team never uses. Then you decide to streamline things and stop updating the artifact. Well, that’s your troubleshooting guide, that helps the support team handle user requests. They don’t know it’s not being updated anymore, they think there’s simply nothing to update. Now more incidents are coming in and they can’t handle them. They ask your team for support. There goes your productivity away (that one you were trying to improve). - You don’t know who will see the measures.

Measures require analysis to be interpreted. This often takes into consideration the context of what happened at a given moment or characteristics of where they come from. One example is comparing velocities from different teams. If a team compares each story to a 2-points story that took 30 minutes to complete and another team compares each story to a 2-points story that took 1 hour to complete, caeteris paribus (all other things being equal), the first team will have a velocity twice the value as the second. If you don’t know who these measures serve, you don’t know what story the numbers need to tell. - You don’t know the behavior you want to stimulate.

Remember our initial discussion, around Campbell’s Law? You want to choose measures that are neutral or stimulate a positive behavior. Positive behavior is one that produces results aligned with goals. If there are no goals to achieve, how do you decide in which direction you want to influence the behavior?

I hope you liked this post. If you have any other insights about this, make a comment below. I read and answer all the comments. :-)

Cheers!